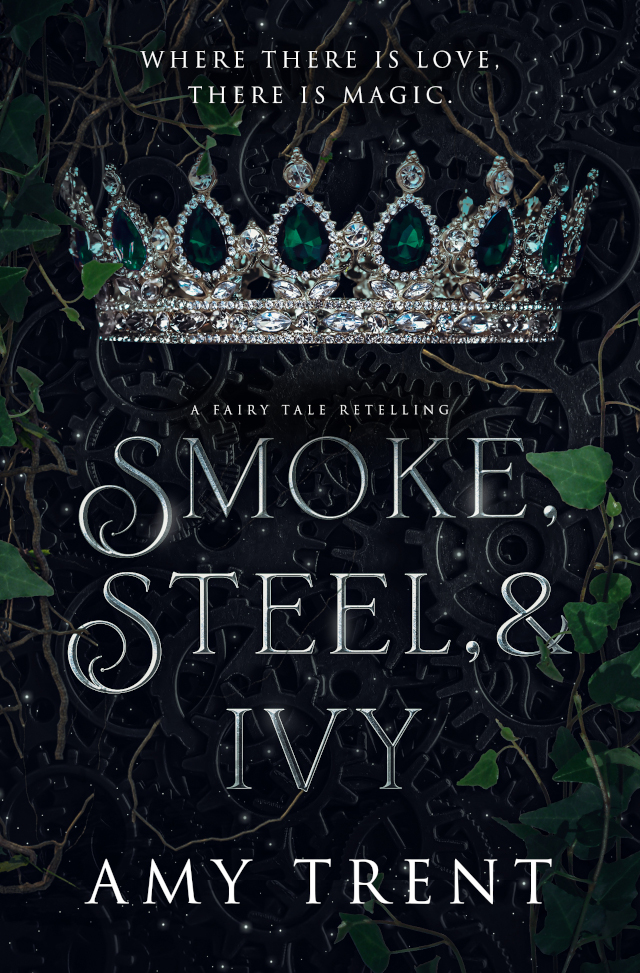

Please enjoy this sneak peak of my first fantasy romance. The novel is inspired by one of my favorite fairy tales, The Twelve Dancing Princesses. ON SALE NOW.

Ivy did not have time for bedtime stories or fairy tales, but she had even less time to argue with her youngest sister. “Once upon a time, our kingdom was so thick with magic, you could hardly breathe.”

Mina pulled her feathered quilt up to her chin. “Was the magic thick like the ice outside on our cherry trees?”

Ivy opened her pocket watch to check the time. If she hurried, she might be able to make a cup of chocolate before the kitchen grew too cold.

“Or was it thick the way you call Papa sometimes?”

Ivy snapped her watch shut and cleared her throat. “They say—”

“Who’s they?”

“People. People like our godmother—”

“Who has fey blood pumping in her veins.”

Yet, Auntie Olivia had not made any such claim in years. Four years, to be exact.

“I wonder if I have fey blood,” Mina prattled. “On my mother’s side, I mean. It’s very likely. My mother’s family tree is much more exciting than Papa’s.”

Not this again. Ivy had no time for a recitation of their complicated family history, made all the more complicated by the web of monarchies that wove its way in and out of it. “They say you can still smell the magic. Even in our capital.”

Mina sighed and nestled into her silk pillows. Mistress Kitty, the rotund, gray house cat, settled into a coil next to her head, purring loudly. “What does magic smell like?”

“Like moonlight. Newly cut grass.” Ivy conjured memories of Amadanri’s capital before the war, before the coal smoke soured the air and sooted the cobbled streets. “Fresh-baked bread. A summer rain right before dinner. Cherry blossoms on a windy day.”

Mina yawned. “It can’t smell like all of that.”

“Well…” Ivy bent down to kiss her sister’s head. “It’s that note they all have in common.”

“Do you believe in magic?”

Ivy tensed. If magic had ever existed, the last of it had fled their country years ago. Probably taking refuge in the Shale Mountains or hiding away in some distant little coastal country to be shipped across seas to safer lands. All that remained were traces in stories and customs, aside from the rumors that the fey still worked in magic. But Mina wasn’t asking for history, and she was still doggedly pursuing the argument Ivy had tried to avoid all evening. Ivy pressed a hand to her forehead. Might as well get on with it. “I can assure you there is nothing magical about the opening night of a new opera.”

Mina bolted upright. “I still want to go.”

Ivy collected the scattered tomes of folklore around Mina’s bed into a neat stack on her nightstand. “Mina, you are—”

“I know. Only twelve.” Mina huffed, and the cat meowed distastefully before jumping with a thud off the bed. “You could have at least let me go to the play tonight.”

“Must we do this again? You are too young. I already have my hands full enough as it is. Next year—”

“What if there isn’t a next year?”

Ivy’s heart hammered in her ears. “What did you say?”

“I saw Papa’s report on your desk. If we are running out of supplies for our soldiers, how long before we run out of supplies for ourselves?”

“Oh, Mina.” Ivy smoothed her sister’s hair. “You needn’t worry over some silly pages. Papa needed my help poking holes in it, is all. He has a plan for peace, and I will tell you all about it. But tomorrow. I must get to work. I have Papa’s appeals to sift through tonight, and you must get to bed.”

Ivy rose and left the apartment she shared with her eleven sisters before Mina had the chance to uncover the truth: Papa had no plan. He had daughters. Twelve of them.

If only daughters could end wars as easily as fathers could start them.

Half a dozen vermilion dispatch boxes, stacked haphazardly on the marble-topped desk in the library, were waiting for Ivy. All the inner workings of Papa’s government were in those boxes—briefings, reports, state correspondence—and awaited his nightly review and approval. But reviewing the boxes was too tedious for one man, so Papa had argued when he conscripted Ivy into service. She’d been more than happy to help, particularly when Papa told her that reviewing the appeals was to be among her nightly duties. Not everyone who committed a crime against the Crown was deserving of their kingdom’s antiquated punishments, and everyone in the Kingdom of Amadanri was granted the opportunity to appeal to His Majesty’s mercy. Magistrates combed the prisons daily to facilitate the honored tradition. It was all to the good, and Ivy was more than happy to apply Papa’s initials to the appeals, setting aside the cases that clearly warranted further attention. But Ivy’s interest in the matter had nothing to do with mercy or tradition and everything to do with ending the war.

She grasped the nearest red box and turned it over. The stack of documents landed with a thud that rattled the library’s leaded windowpanes.

Trina startled, though she did not turn from her spinet. “Ivy!”

“Apologies,” Ivy murmured, leafing through the stack. “I thought you might be at the play.”

His story was hiding somewhere in Papa’s box of appeals. Buried among the heart-numbing tragedies was a man with nothing to lose and a soul for sale. Ivy needed to find him soon, or else… Mina would be right. Ivy sighed. Summarizing the findings of the day’s briefings and reports into a single, legible page came first. She wouldn’t have the necessary focus otherwise.

Trina experimented with a chord progression. “You missed dinner.”

The ice-covered branches of a bare cherry tree clacked against the library window as the wind howled low and long and mingled with the notes of Trina’s spinet. A weak smile played across Ivy’s lips. It was sweet of her sister to move the instrument down to the library.

Trina played a few measures. How she could infuse such feeling into a few notes was beyond Ivy’s understanding. “Pen said to tell you your machine is ready. I told her to bring it by after the play.”

“Excellent.” Ivy scribbled a note in her dossier. She’d fight for increased winter rations in her summary. “Did Pen mention if she’s tested it?”

“On every last one of us. Except you.”

Ivy sighed. The flood of papers was never-ending. All of them important. All of them, Papa insisted, needed to be reviewed by another set of trusted eyes. All of them kept Ivy up at night and busy during the day. “I promise you’ll see more of me when the war is over.”

“If it ever ends.”

Ivy cringed. That was the problem they were up against. The war, a disordered disaster, would grind to a bleak defeat when the snow melted, unless Ivy could succeed where their best generals had failed. “Did Sophia have a go with Pen’s data?”

Trina laughed.

She’d take that as a no. “Would you ask Sophia to play with the numbers? Tell her variance and correlation.”

“In exchange for?”

Ivy flipped through a new report detailing projected shortfalls of black powder. “My thanks and unyielding affection.” She wished there’d been a report projecting when their weapons would become obsolete. Never mind, she knew the answer. “And if that doesn’t work, my lavender brooch.” Ivy moved the candles closer, though the smell of hot wax quickly made her second-guess the merits of her supper of cocoa and mints. The library needed more electric lamps. “Heaven knows I won’t be needing it,” Ivy mumbled.

Trina paused her playing. “The acoustics in here are better than I remembered.” She scribbled a note on her sheet music.

Ivy never would have asked her sister to join her, but she was grateful she came. “Yes, the echoes keep me company.” She grabbed another appeal. “The books too.”

“And, of course, the statue of Adonis.”

Ivy rolled her eyes and flipped to the end of the report. “Did you know the triplets asked to have him moved to our apartment?”

Trina’s laugh was as musical as the rest of her.

Ivy’s grip tightened on her fountain pen. Trina could still laugh. She could still enjoy her music, her days, even her evenings. The truth could swallow Ivy whole, as long as her sisters were happy. She would shoulder every inconvenience, every burden, to keep them as far from the war as possible. But she couldn’t do it alone anymore. She needed help. Someone desperate enough to join her. Someone for hire…

She’d repeatedly scoured the ranks of their own soldiers for such a man, but had not found him. Earlier this winter, she’d persuaded Papa to send any colonel who could be spared in search of an officer who had the skill set she needed. All her most promising leads had literally come to dead ends, yet one or two of her persons of interest were presumed AWOL—a criminal offense against the Crown if they were ever found alive. Desperation had Ivy combing through the appeals, hoping against reason such a man would turn up in their prisons ready to make a bargain.

“Ivy darling.” Ivy hadn’t noticed when Trina had left her spinet, but her sister was now standing at her desk with a report in hand. “Why are these frostbite statistics from the front on your desk?”

Was every sister in the house suddenly interested in the war effort?

The reason for Ivy’s involvement with the reports was simple enough—the news was terrible and tedious, and Papa did not deal well with either. It was Ivy’s job to sift through all the bleak information contained in Papa’s boxes, apply his initials, identify actions that must be taken, and make sense of it all in a succinct summary that Papa could peruse at his leisure the following morning. Preferably after his breakfast.

Ivy took the report from her sister and set it aside. “When soldiers lack proper boots”—and functional weapons, ammunitions, rations, and fuel—“the cold can be dangerous.” She tucked an arm around Trina’s shoulders and gently steered her back to the spinet. “This is why I want Papa to agree to my new strategy.”

“Enough, Ivy. We are practically the same age—”

“Still ten months your senior.” Ivy bussed the empty teacup from Trina’s spinet to the sideboard.

“—so you will tell me the unvarnished truth.” Trina’s playing tumbled to a thin pianissimo. “How bad is it?”

Ivy poured her sister a fresh cup of peppermint tea. “It’s not good.”

Trina’s music stopped. Fear pooled in the shadows of her face.

Oh no. “But it’s nothing for you to worry about.” She swirled in a spoonful of honey.

“What are we going to do?”

“Well…” She set the cup and saucer gently on top of the spinet. “Our boys have fought hard. Now they’re safe behind snowdrifts and iced roads.” To say nothing of the enemy’s frozen rails. “It gives us just enough time to rally.”

“Can we?”

Ivy picked out a simple C major on the spinet. “Resourceful minds always rally. It’s a matter of getting the right people and the right tools together.” Ivy had lost her touch for this. Reading too many reports in which lives lost were distilled to numbers and statistics would do that to a young woman. It’s why she was so eager to propose a different approach. But Papa had refused to hear her. Again.

Trina took a sip of her tea. “Is that why you insisted Pen make your funny little machine?”

Not exactly. Ivy returned to her desk and scribbled Papa’s initials at the bottom of another briefing, this one detailing the dwindling grain stores. Hardly a surprise. The draft had taken nearly every farmer from their fields. “The heart is a metronome.” Ivy removed her spectacles and rubbed her eyes. “If its beats are cataloged on paper, I can eliminate uncertainty.”

“What sort of uncertainty?”

Ivy replaced her glasses and reached for the next briefing. A lengthy report on sustained mental trauma, accompanied by stress, among the wounded and honorably discharged veterans. Gracious. What would happen when all the soldiers returned to civilian life? “Human error.”

Trina shook her head. A cacophony of sounds flowed from her fingertips.

Ivy initialed the report and grabbed the next. “If I had a map of a man’s beating heart, I could tell you when he was lying. If I could log the numbers against his respiration, I could know he was hiding something without him saying a word.”

“If you get to know a man, you can tell when he’s lying without a score of his heartbeats.”

A blond pixie of a young woman kicked the library door open wide. “Unless he’s like Pops, and lying is his native tongue.”

Ivy’s younger sister, Pen, marched into the library carrying a smart-looking steel box with an assortment of tubes and wires piled on top of it. “I don’t know how you do it, Ives.”

“You learn to discount everything he says when he opens his mouth.” Ivy scrawled Papa’s initials in the corner of the report, then rushed over to her sisters at Trina’s spinet.

“I meant I don’t know how you do that,” Pen said, dragging a chair closer.

“The boxes?” Ivy asked.

“The pages of cramped squiggles. I’d sooner go blind than spend all my waking hours looking at them.” Pen set the machine on top of the spinet and began connecting the tubes.

“How was the play?” Trina asked.

“Rubbish. I only went to see Sophia and the triplets charge the actors afterward. That was spectacular.”

Ivy pinched the bridge of her nose. “I’ll have to have a word with them.” Chasing after young actors was a recipe for scandal.

“Don’t bother,” Trina said. “They’re determined to carry on Papa’s tradition.”

“Agreed. Now…” Pen patted the chair. “Have a seat, Ives.”

Ivy complied.

“Two tubes around the chest. They measure breathing.” Pen strapped the tubes around Ivy. “Wires connect to these bits of metal that rest against the temples.” She placed the leather strap with connecting wires around Ivy’s head. “A cuff to measure the pulse on the right or left arm. And more wires to wrap around the forefingers.”

“The point of the wires being?” Ivy asked.

“Tracking eye movement and perspiration.”

“Ingenious!” Ivy winced. “And uncomfortable.”

“You have to stay still,” Pen said, attaching the last of the wires to Ivy’s fingers. “Now then, Trina, ask away.” Pen clasped Trina’s shoulder affectionately. “Remember, yes or no answers only. Better make them easy for her.” Pen’s trademark smirk surfaced.

Trina took a sip of her tea. “Is your first name Ivy?”

“Yes.”

The machine began to whirr, and modest squiggles appeared on a rolling feed of paper.

“She speaks the truth!” Pen beamed.

“Is there a young gentleman who inspired this machine?”

“Trina!” Ivy said.

“Yes or no answers, if you please,” Pen said, pressing her lips together, her eyes twinkling.

“No,” Ivy said.

The sisters peered at the machine’s tracings. The squiggles had grown. Considerably.

Pen’s eyebrows wiggled. “You looking to audition an assistant?”

Trina giggled. “Perhaps a tall, dashing one?”

Ivy’s heart beat faster. The squiggles grew frantic on the machine’s tracings below. “All right, you’ve had your fun. I need to get back to work. And the two of you should get to bed.”

“So bossy,” Trina said.

“Typical eldest child,” Pen agreed, turning off the machine.

Trina closed her spinet. “Remember you have a bed too, darling.”

Ivy twisted the wires off her fingers. “I can’t sleep. Not until I’ve reviewed all of Papa’s boxes. I’ve got his appeals to consider too.” Maybe tonight there’d be someone promising among the typical horse thieves and drunk-and-disorderlies.

“If Papa doesn’t review his boxes, why should you?” Pen asked while she disconnected the remaining tubes and wires from Ivy.

“Papa does review the boxes. He just needs a second pair of trusted eyes, is all.”

Pen tore off the tracings and handed it to her sister. “Papa riffles through the boxes looking for fan mail.”

“Or invitations from favorite courtiers,” Trina said with a yawn.

Ivy tossed the tracings on the desk and grabbed the box of appeals. Anything not to look her sisters in the eye. “Papa is a busy man.” Although, Ivy must admit, it was not the monarchy or the war that occupied his days. “Someone needs to champion mercy. Half a dozen innocent men have been granted clemency this winter alone.” Ivy brushed her dark curls away from her face. The truth gnawed at her, but if she told Trina and Pen, they’d be plunged into needless worry. She wouldn’t do that to her sisters. Not now. Not ever.

Ivy thanked her sisters, insisted she must get back to it, and wished them a good night. Alone once more in the library, she sifted through Papa’s boxes until only the box of appeals remained.

The grandfather clock echoed the late hour. She checked the time against her pocket watch. Three minutes slow. Ivy poked the fire. It crackled a reproach of sorts but wrestled out of its cozy embers. She tossed in a log and rubbed her palm against her pinstripe skirts.

Ivy read through the appeals, disheartened by the guilty and innocent alike. She scrawled Papa’s initials on the majority of the appeals, indicating he agreed with the sentencing, but made a modest stack for the secretaries of the men she believed deserved more careful consideration.

One last crumpled note lay on her desk, a receipt of sale of some kind. The magistrates were a sloppy lot, but if Ivy was anything, she was thorough. She downed the last sip of her now-cold cocoa and smoothed the note flat.

A barrel of spiced wine and three shearlings transferred…

Gracious, the note was from last summer. Ivy flipped it over and saw three paragraphs of writing in a tight, neat hand.

Ivy read aloud. “‘I petition His Majesty for mercy as the circumstances of my arrest were not considered during my sentencing.’” Ivy’s finger fell to the recording stamp bearing yesterday’s date at the bottom. So it was an appeal, but not an appeal drafted with the assistance of the usual court magistrate.

His Majesty must be made aware that until my arrest I served with distinction.

Ivy’s heart began to race.

Captain in the north regiment.

Her tired eyes dashed and jumped across the page, pulling out bits of crucial information.

Extensive knowledge of explosives.

That was good. That was very good, but not enough, given the risks. Ivy’s finger raced across the lines. Until at last she found it.

Sentenced to life in prison.

Ivy fisted the appeal into her dossier, which she tucked under her arm. She grabbed Pen’s machine and raced out of the library.

This man—imprisoned, coldly articulate, and furious—could be the key to saving the kingdom and winning the war, if Ivy could persuade him to try.

Collin strained against the leather belts and cuffs that fixed him to the metal chair. He did not like sitting with his back to a door. Never mind the nerves—all that twisting to try to catch a glimpse of who was walking in and out was brutal on the neck. Then again, his discomfort might have more to do with yesterday’s torture.

“Please, don’t struggle.”

Who strapped down not only a man’s arms, but also his ankles and head, and then said the word please?

Electric lights hummed from the vaulted ceiling of the crypt. Wires wrapped around Collin’s temples and threaded back to the box of gears at his side. The steam that hissed from the boiler… That was a far more pressing concern. The noise muffled entire catalogs of sound. The condensing steam on his skin distracted him, made his mind wander to concerns—chiefly, the electrical conductivity of water.

The boiler presented too many distractions for collecting reliable information.

And collecting information was all that mattered now.

Collin cleared his throat. “Is all this really necessary?”

The sharp sound of well-heeled boots clacked against the slick grave markers on the crypt floor. “Yes, they are necessary.”

They’d sent a woman. Marvelously good of them to find one with such wonderful perfume. Orange blossoms and jasmine, with a hint of chocolate. “I meant converting the abbey’s crypt into a noisy boiler room. Haven’t the dead earned their peace?”

“Progress is no respecter of persons, dead or living.” A pen scratched, and papers shuffled. “More importantly, the war has limited our resources.” The click of a pocket watch opening and closing. “In more ways than you know.”

“Hence the makeshift interrogation chamber and homemade tinker toys?”

A rustle of skirts and a huffy sigh. “This machine monitors your beating heart, the strain of your blood through your veins, even your respiration, and transmits the information pictorially.”

“To what end, madame? Or is it mademoiselle?”

The woman bent to examine the scribbles, but Collin caught no details. Maybe ink-black curls. The yellow glow of the lightbulbs made it hard to tell. “To put it simply, this machine tells me if you are lying.”

Collin snorted. “You need a machine to tell you if a man is lying?”

“No. I need an excuse to tie you up.” Collin’s interrogator stood before him now. She was a young woman. Her hair was dark and piled on top of her head until it tumbled down her back. She had dark, lovely eyes—sharp and intelligent, though maybe a little small. Her mouth, though, more than made up for that. Defined. Expressive. Full. And those gorgeous lips twitched into an amused pout. “One learns caution when she has a disadvantage of three stone.” The young woman ran her fingers slowly, carefully across the box of gears. “And it is fun, isn’t it? Advancements. New toys. Technology civilizes us.” She returned to scratching notes in her dossier. “It’s proof of our refinement.”

“And here I thought it was mercy and brotherly kindness.”

The young woman’s lips flattened into a firm line. “You will answer each of the following questions with a yes or no answer. Do not speak otherwise. Now, then, is your surname Dobhareach?”

Collin sighed. “Yes.”

“And is your name Collin of Thuaidh Fuar?”

“Yes.”

“Is your name Meleager?”

Why not? “Yes.”

The young woman bent over the tracings and scoffed. “They can’t all be your name.”

“Well, they were at one time. I wear names out rather quickly. Much faster than the average man.”

“Yes or no answers, Mr. Dobhareach, or would you prefer Mel?”

“No, that was at least two names ago.”

She flipped through the files in her dossier. “No wonder I didn’t find you sooner. Half your aliases are presumed dead.”

Collin’s chest tightened. She’d been looking for him?

His interrogator continued. “Are you a citizen of His Majesty King Rupert the Just’s Kingdom of Amadanri?”

“Yes.”

“And were you a captain in His Majesty’s royal army?”

“Yes.”

The young woman paused and bent over the machine’s tracings. She brought the spectacles that hung from the chain around her neck to her eyes. “Either you are comatose or more practiced at telling the truth than any man alive.” She straightened. Her clever fingers checked the wires connected to Collin’s temples.

Collin watched in silence as she paced in front of him. She was tall, but her frame was slight. The black, pinstriped skirts that were bustled dramatically, as well as the impeccable tie around her throat and carefully tailored cut of her blouse and vest, gave only the illusion of age and experience.

“Something wrong with your machine, mademoiselle?”

“Unlikely.” She scribbled a note in her file. “Then again, it is possible that an external source of stress is necessary for calibration in this instance.” Her lips twisted into a deathly smile.

“What is your age, Mr. Dobhareach?” Before Collin could answer, the woman took a perch on his right knee. She was sitting in his lap and staring at him with her onyx eyes.

Collin swallowed. He felt moisture slide down his back, but he doubted he could blame it on the steam in the room. “One and thirty.”

“You are thirty-one years old?” She briskly smoothed her skirts.

“Yes.”

“I have here in your military record that you were twenty when you enlisted four years ago.” She shifted her files to rest a hand on Collin’s shoulder. “Are you sure you are thirty-one?”

Her clothes made a lovely crinkling sound when she moved. And her hands, small though they were, had a weight to them that was distracting. “I suppose I wear my years out faster than the average man too.”

She laughed. And Mars, she was a prism when she laughed. Just like the ones Gran used to hang in the windows when he was a boy. She absorbed Collin’s carefully collected theories and reflected them back as a pretty puzzle of uncategorized thoughts and emotions. Distracting thoughts about wanting to hear her laugh again and learning her favorite dance.

“Are you twenty-four?” she asked.

Commitment was important. So was keeping this woman as close as possible for as long as possible. “No.”

She leaned over to examine the graph that now had some admirable squiggles across it. “At last!” Her voice fell into the comfortable register of satisfaction. “It would appear that the introduced stress to our little interview has more accurately calibrated your responses.”

“Meaning?”

“I’ve caught you lying. You are twenty-four.” She flipped through some of the records in her dossier—but stayed on his knee. “Although I must admit I am surprised. No one would believe you’re only two years my senior.”

“Charming.”

“Now, then, let’s talk about desertion.”

Collin swallowed. The back of his neck prickled. “If you insist.”

The woman studied Collin’s face. She gently pulled free his hair trapped underneath the leather strap. He’d been wrong about her eyes being too small. She was lovely. “I understand that you disobeyed the orders of your commanding officer, abandoned your post, and deserted your men. Is that not so?”

“Yes.”

“I can’t abide a coward.”

“I suggest you reverse that opinion. We need more cowards in this kingdom.”

The mademoiselle was once again fidgeting with the wires at his temples. Her fingers felt electrifying against Collin’s skin. “Is that so?”

“Yes.” Collin spoke with conviction. Her fingers paused. “My order was to execute a couple of farm boys turned Olcceart fighters. I refused.”

“Why?”

“I have too much respect for human life to do anything so stupid.” Collin closed his eyes, trying to shut out the fear-drenched memories. He needed to concentrate. Not easy to do when an attractive young lady was sitting on one’s knee. “One day, this war will be over. The enemy will be our neighbor.”

“Unless he is our dictator.”

“We will need those two farmers for the bread they grow.”

The woman arched an eyebrow. “Farmers do not grow bread.”

“You understand my point.” Collin winced against the high-pitched whine that started in his ears. “The senseless slaughtering on both sides must end immediately. Our people need to buy and sell goods somewhere. Our kingdoms are too small to exist independently. We need each other.”

“And what do you need, Mr. Dobhareach?”

“I need you to untie me. I’m far more persuasive with my hands free.”

The woman rose. “Are you a hero, Mr. Dobhareach?”

Collin swallowed against the swell of panic. He felt it rattling inside, close to taking over. “I could be, if you like.”

She wasn’t the sort to blush, but she was the sort to smile wickedly into her folder of notes. “You were decorated in the Battle of Amaideach. Not a single man of your company was wounded, and such a decisive victory. Your strategy was brilliant, yet unconventional.”

“Human life is the most important commodity on earth. Far more precious than weapons or gold.”

“Explain to me how you managed to disarm an insurgent group that outnumbered you three to one?”

“While the parties called a cease-fire to resupply at the river, I infiltrated their ranks, targeted their armory, and destroyed it.”

“Not very sporting of you.”

“It’s a bloody war. Both sides are trying to kill each other. It doesn’t have to be sporting. I found a solution without shedding a drop of blood.”

She was pacing once more. “Burning an armory is risky during a cease-fire.”

“It didn’t happen during the cease-fire.” The squiggles on the machine’s tracings were growing larger.

“How did you—”

“I planted a timed detonator.” Collin twisted his wrists against his restraints until the leather bands dug into him.

“Controlled explosives?” She nearly dropped her dossier. “I’ve been trying for years to persuade—”

“Who are you?” Collin asked.

The mademoiselle startled and blinked. “I’ll ask the questions, Mr. Dobhareach. Where did you study explosives?”

“Gran fancied me a surgeon.” Collin winced. The wires at his temples pinched. “But the apprenticeship required connections and resources we didn’t have. So Gran farmed me out to every chemist in our town, not to mention hatters, tanners, cobblers, soapers… She hoped it would be enough to get me into the army’s medical corps.”

“Was it?”

“Yes.” Collin shut his eyes tight against the memories. He wished he could shut his nose, his ears. “My talents and experience lent themselves better to the inorganic.”

“Elaborate.”

He could hardly breathe. There were too many memories too close to the surface. “Chemical combustion.”

The young woman flipped to a different page in her dossier. “Yes, your regimen’s armory had a considerable store of grenades, shells, and other incendiaries.” She snapped the dossier shut. “Yet, our stores of black powder have been depleted for months.”

Collin shrugged. “Charcoal, sulfur, and saltpeter are not the only chemicals that combust.” Truthfully, they were not even among Collin’s favorites. “I improvised.”

She laughed, but this time it was a single beat of dismayed wonder. “I take it those lumps of putty in the armory were something dangerous?”

“Not on their own, but with some persuasion.”

“A detonator?”

She was a quick study. “Yes. What are you going to do?”

“With the putty?”

“With me? I’ve been questioned before. And yes, I enjoy your brand of interrogation much more than the old dandy who insisted on slapping me, but to what end?”

She took a deep breath and twisted her spectacles chain between her fingers. “You’ve been charged with insubordination, desertion, and treason.” She fumbled, and the chain slipped out of her fingers. “Ordinarily, life in prison would be the consequence of such actions, but your experience and skills cannot be ignored. It is as you say—we need more cowards in this war. We are running out of manpower. We need a clear strategy and a decisive victory to force a peace, and then we need everyone back in the fields so we can at least harvest some potatoes come autumn. We need our men back so that there will be babies again next spring. The birth rate has fallen at an alarming rate—”

Collin groaned. It was always the simple, albeit disappointing, answer.

The young woman tore off the tracings and went about adjusting the toggles of the machine. “You seem to be our only dog left in this fight. Believe me. I’ve been looking for ages.”

She was standing in front of him, so he could see it now. Stupid, really, not to notice it earlier. “You have a sweetheart fighting out there, don’t you?” Probably a celebrated but completely incompetent baron turned petty officer. “You hope to have a baby of your own come next spring. Who are you doing this for?”

She flinched before she tossed a loose curl out of her face and straightened. “I should ask you the same question. Your record has no family listed. Your wages were sent to a poorhouse in Durbronach before they were garnered.”

The whining in his ears had distilled to the sound of his own pounding pulse. Collin arched his back and dug his nails into the cold, wet metal of the chair arms as he strained against his scientific fetters. “Look,” he said in a voice louder than he’d intended, “I’m going to break your clever machine if you don’t untie me. My patience is worn out.”

“Calm down. I’m nearly finished.” The woman peered at the squiggles of the machine’s tracings and opened the case of her pocket watch. “Excellent. I won’t have to sit on your knee again.”

“We wouldn’t want to upset your man in uniform,” Collin mumbled.

“Brilliant, Mr. Dobhareach.” She scribbled in her dossier. “Distilling an armed conflict that has lasted these four years, not to mention the pain and suffering of countless souls, into a woman pining for a presumed sweetheart.” She gripped her pen until her knuckles turned white. “Brilliant,” she repeated through clenched teeth.

Collin’s simple construct shattered. Exactly like Gran’s favorite prism had when the explosions started. All that colorful light disappearing instantly into countless shards. Collin’s mind raced to fit the shattered pieces into a working theory.

“I want peace, Mr. Dobhareach. Peace for us all.” Mars, she’d become almost wistful.

“Why me?” Collin asked.

She raised an eyebrow. “I need someone I can trust.”

He scoffed. “You’d trust a deserter?”

“No. I trust tight leashes.” The young woman snapped her files shut. “Your appeal is impossible. No one likes a coward—desertion, et cetera. Clemency in this case would be a scandal. I’m afraid you will live out the rest of your life in prison.” She brought forth the tarnished pocket watch, rubbed her thumb against the surface. “Unless you agree to help me. Then you’d be a hero. A gallant and dedicated officer with a strong moral compass who has always obeyed a higher law and turned the tide of the war.”

“There were witnesses to my insubordination. You can’t just rewrite—”

“I’m very persuasive with a pen.” She replaced her watch in her vest pocket. “If you help me, join my task force, the charges against you will be dropped. You’ll be a free man after the war. Do we have an agreement?”

Collin rattled his fetters. “And in the interim?”

Her eyes narrowed.

“My wages have been garnered during my stay in your capital prison. I’d like them back. With interest.”

“And, no doubt, a raise?”

“Fifty percent. It’s a small price to own a man.”

The woman bristled. “I don’t like your phrasing.”

“Eighty, then. To drive home the ugly truth of our bargain.”

She paled. Her lashes fluttered, and her boot skidded slightly against a gravestone as she took a step backward. “You’re in no position to make demands.”

“And you’re more desperate than I realized. Three hundred percent and a farm on the outskirts of the capital when all this is over.”

Her chin trembled. “You’re not the only man to appeal to His Majesty.”

But she had let slip that she’d been looking for someone like him, probably for some time. The steam hissed from the boiler and settled on the uneven stone floor. “You forget I served for the past four years in the army. I’m well aware of the talent pool you have to draw from. I am one of the last explosives experts left with both his hands and all his fingers.”

“And a beating heart.” She opened her dossier and scribbled a note. “Fine.”

She bought it? The straps bit into his skin as he struggled to sit upright. “You really think I can help you win the war?”

She froze. “You have to!” She spread her shaking hands wide and gestured around her. “This all crumbles away if you don’t. We end. All of us! There’s nothing I can do about it alone. And believe me”—she clutched her dossier and raked a trembling hand across her cheeks—“I’ve tried everything else.” She shut her eyes tight before smoothing the front of her vest. “Others may be content to pretend there is no immediate danger. I know otherwise. Now.” She tried to catch her breath and piece together her courage, her armor of composure. “Will you swear your allegiance to King Rupert?”

“That’s impossible. The man is a selfish, incompetent disaster. Not to mention an ugly, beady-eyed toad—”

The door scraped open, and the guard appeared. “I heard shouting, Your Highness.”

Oh.

Collin winced. He was an idiot.

“Thank you, Constable. I’m almost finished.”

The door slowly creaked shut once more.

“I can’t grant your appeal unless I can vouch for your allegiance.”

“Then let me swear it to you.” Collin swallowed and looked up into her face. “Princess.”

Princess Ivy, eldest of King Rupert’s twelve daughters, tore the final tracings from the machine and exited the crypt.

The door to the crypt needed replacing, oiling at the very least. The hinges shrieked with every swivel. It was almost enough to keep Ivy behind them.

She pushed through the door. “Constable.” Ivy willed her voice not to shake. “Mr. Dobhareach is to be taken from the crypt and detained in the abbey cloisters until I return.”

“Very good, Your Highness.”

Ivy tried to smile. Papa was always getting after her about her frown. “Constable Jefferies, is it?”

The man nodded.

“Mr. Dobhareach is not to be harmed.” Ivy’s stomach twisted at the thought of the young man’s purple and yellow bruises.

The constable bowed.

“Thank you, Constable.” Ivy added the final tracings to her dossier before she buckled it shut. She only had to march one foot in front of the other, and then it would be over. Sunshine was at the other end of those dark, narrow stairs. Once she felt the warmth on her skin, she’d be able to breathe again.

It didn’t sit right with her. She’d needed the demoted captain to sit still for her machine to work, but she hadn’t needed him shackled to the chair like some animal. The fact that she’d felt so much safer because of it was appalling.

Her hands still shook as she crossed the lawn between the abbey and the palace. It was too cold and too early for anyone to be on the commons. The wind blew hard with all the strength of winter’s bitterness. It carried the endless, inescapable coal smoke of the capital to her face, triggering tears. Good. The wind could be blamed for her tears today. She’d put them away as soon as she stepped inside the palace.

Bluffing was all she had. And she’d failed. No one respected a little girl who cried in a corner and begged for help. She needed to be strong. She needed to demonstrate experience and confidence, and she’d done a passable job. Until the end.

He’d asked for reassurance of her faith, as if it were commonplace to put her trust in a deserter. As if there were nothing concerning at all about risking everything on a man who knew his way around a timed detonator and had refused to swear allegiance to the king.

But he had instead sworn it to her. Ivy’s skin prickled with the memory.

Ivy knew what she was risking. She knew that the coal smoke could, in a matter of weeks, turn into the smoke of burning buildings. And souls.

He’d looked for faith. Instead, he’d found her raw desperation.

Ivy patted her cheeks dry and pushed open the kitchen door. The kitchen whirred with activity. The servants moved with the familiar purpose of a busy house.

Frankfurt, the butler, bowed as low as his old back would permit. “Good morning, Your Highness. Any signs of spring sunshine this morning?”

“None that I could see through the coal smoke.” Thank heavens for that. Ivy needed all the time winter could buy. “It’s as cold as any winter day I’ve known. I wouldn’t be surprised by more snow.”

“Maybe so, but I am an eternal optimist. Early springs do happen. Cup of chocolate, ma’am?”

If only there were time. “No, thank you. But, Frankfurt, I feel a distinct draft.”

“The chimney, ma’am. It was damaged in our last storm, and on windy mornings like these, we feel and hear the damages. Mrs. Stoddard has spoken with Her Majesty.”

But of course to no end. Ivy opened her dossier and scribbled a note in the margin of Mr. Dobhareach’s final tracings, right under the terms of his aid. She’d have to review the household budget again. Hopefully, willful neglect, and not a lack of funds, was the reason for the delayed repairs.

“Is my father taking breakfast—”

“In his apartment, ma’am.”

Ivy nodded her thanks and quickly made her way out of the frigid kitchen.

***

King Rupert sat hunched in his special chair. Not the throne. That was too old and dirty, not to mention uncomfortable, for day-to-day. King Rupert liked his luxuries—gilded wood carvings on all the paneling, silver mirrors with gold leaf frames, heavy wool rugs from the Easterlies, and fine silk cushions stuffed with goose down.

“I don’t understand why I can’t have a footstool to match,” King Rupert said with a mouthful of eggs and lox.

“Papa, it speaks so plainly of the boudoir,” Ivy said.

“If I want a footstool, I should have a footstool.”

“And if you wanted to conduct matters of state in your dressing room? Or in your bedchamber?”

“Then I should do it.” King Rupert’s jowls hung like those of a mastiff. And something about the dim glow in his eyes was faintly reminiscent of one too.

“Papa, it wouldn’t be appropriate for courtiers or dignitaries to follow you into your personal areas.”

“Oh, they don’t care if I don’t care.” King Rupert frowned and added generous spoonfuls of salt to his eggs.

“Papa, I wondered if you, or perhaps Adelaide, have approved the repairs for the kitchen chimney.”

“You’ve interrupted my breakfast for a smoking chimney? I am the king, Ivy.” He gestured with his hands. Always with the hands when he was frustrated or blundering through political duties. “I don’t have time for petty problems. Don’t I have my hands full enough with the succession crisis?” He shoveled another bite of eggs and lox into his mouth. “And the war?”

Ivy gripped her dossier tightly. She didn’t need another lecture on the war. “Of course you do, Papa.”

The king licked his fingers before mopping his mouth with the vermilion linen. “What do I say? What do I always say?”

“‘Bring me solutions, not problems.’” At last, Ivy had a solution. A great big important solution that could save not just lives, but the entire country. “Papa, there is a man I want you to meet.”

The king spread inordinate amounts of marmalade on his toast. “Have I told you about my opera?”

Ivy swallowed. She’d learned long ago that her father would not consent to tedious political discussions unless every one of his current pet projects had received the appropriate care and attention.

“Opera?” Ivy poured herself some cocoa from the sterling chocolate pot at the sideboard. King Rupert was enormously fond of his sweets. Particularly on dreary winter days such as these.

King Rupert smiled up at his daughter. A more satisfied smile didn’t exist in all the Shale Mountain realms. “I wrote an opera.”

“Papa, that is wonderful.” Ivy stirred her cocoa but remained standing at her father’s side. He’d not invited her to sit. “Tell me all about it.”

King Rupert nodded. “I wrote the lyrics. You know I’m a sensitive, introspective man.” He picked up the knife on the table and began cleaning his nails. “I wrote the lyrics, and Minister Rosecrans begged to see them.”

“I have no doubt.” There could not be a more sycophantic courtier than Rosecrans.

“I wrote it for Adelaide, you know. She is so fond of the opera.”

Adelaide was also fond of her solitude. “Yes, but—”

“Minister Rosecrans was so enamored with my lyrics that he immediately commissioned a score and instructed the royal theater company to perform it.”

Oh dear. Ivy sipped her hot chocolate and flinched. It was far too sweet. Perhaps there would be enough time to salvage the situation. Ivy would have a word with the head of the opera house and persuade him to perform a different opera. Berlios was talented—his wife, Gilda, even more so. The pair of them could rewrite an aria, translate it into a different language if necessary. One pretty little song would be enough to satisfy Papa. He was, after all, merely looking for a creative outlet, an opportunity to impress Adelaide.

“That is wonderful news. I can’t wait to hear it.” And that was entirely true. The sooner Ivy understood the details of the situation, the sooner she could manage it and protect all parties involved.

“I can’t either. The first performance is tonight.”

Ivy choked on her chocolate, spilling quite a bit of it on her tie. “Tonight’s opera? The new opera? It’s your opera?”

“Of course it’s my opera!” King Rupert narrowed his eyes. “Is that so shocking?”

“It’s just…so soon?”

“Well, it’s been in the works for some time. To tell you the truth, I’d forgotten about it.”

Ivy’s heart beat fast. “Well, that can’t be helped. You’re a busy man, Papa.”

“Made all the busier for smoking kitchen chimneys.”

“Might I inquire what inspired the opera?” She set the cup and saucer on the sideboard and blotted her tie with a spare linen napkin.

King Rupert’s brow furrowed. His elaborate, curled wig slid dangerously forward. He no longer wore the powdered ones. These days, he favored the blonds. “Horses.”

Ivy’s heart sank. “Horses? Well, they are beautiful, noble creatures.”

“No. I was thinking about the big, fat ones.”

The mantel clock ticked bravely, and King Rupert chewed his crunchy marmalade toast. “You wrote an opera about big, fat horses?” Ivy asked.

King Rupert nodded. “And the star is a horse who thinks he’s not big or fat enough, but the prettiest horse falls in love with him, and then it turns out that he was always the biggest, fattest horse of them all. Do you think Adelaide will like it?”

“I’m sure it will leave her speechless. Have there been many rehearsals? Surely you must have attended one or two?”

“Oh no. Of course I was kept apprised of the progress, until the reports proved too tedious to keep up with. I approved the budget. They were all so worried about creating all the horse costumes, but I said, ‘This is for your queen. I want you to spare no expense and make this the finest opera this country has ever seen.’”

An ache crept down Ivy’s neck into her spine. Why hadn’t she reviewed the budget this season? She’d asked, but Papa had insisted it was taken care of. She should have insisted. What had possessed her to neglect the financials, not to mention the opera house? If only she had stopped by, she might have learned something telling. Her sisters went to the opera all the time. Of course, they would not have known what to look for. Trina would have been too mesmerized by the music to notice anything amiss. Beatrice, too, if there were any passable flutists, and there always were. Jade would have spent all her time poking holes in the plot. Pen would be beside herself, observing all the “social irony,” as she called it. The triplets and Sophia would have had eyes only for the young gentlemen. Poor dears didn’t have much to look at these days. The younger set would have fallen asleep. Little Mina was still too young to even attend.

Not one would have thought to approach the director afterward to excavate what that telling note of panic meant in his voice. Not a one would have sought out Gilda to learn what was keeping her up at night. Because they didn’t have to. That was Ivy’s job. They could go to the opera and enjoy themselves. Ivy would go, and her mind would only wander in the dark as she worried about whether the opera’s budget allocation might be better spent in rural schools or in research for the war effort. Confound the war!

“Now, Ivy, you said you had someone you wanted me to meet?”

“Yes, Papa.” At last, she could show King Rupert the contents of her dossier and win approval for her plan.

“Good. Bring him to the opera tonight.”

“No, Papa. That is not a good idea. Now, if we could look at my proposal—”

The king waved the proposal away with his fork. “Well, of course it is a good idea. It is my idea. Bring him to the opera. It’s good to mix a little business with pleasure.”

Ivy was sure it was not.

“Gran, are you magic?” Little Collin asked.

How Gran fumed. If Collin’s face wasn’t already bruised, Gran would have boxed his ears. As it were, she banged the pots on the stove until she could speak. “It’s not magic. It’s information.” She slapped a ball of dough on the table in front of Collin.

Collin floured his hands and began to punch and roll the dough until it lost its tackiness.

“Information is all that matters.” Gran dropped the rolling pin in front of Collin. “Repeat it back to me.”

Collin grabbed the pin and struggled to tame the dough into a flat circle. “Information is all that matters.”

“That’s right,” Gran said. Her temper once again returned to a controlled simmer. “You tell people what they want to hear, you make them happy, and they pay you.”

“How do you know what they want to hear?”

“You listen. You watch. Context, Collin. Say it!”

“Context.”

Gran took the big knife and began to cut the flat circle of dough into an odd jumble of shapes—all of them four-sided, none of them squares. “How something is said, what isn’t said, how the body is carried. It matters! You gather the pieces of information together…” Gran’s callused hands had a natural tremor to them, like the fiddlers who came through town in autumn. Except Gran didn’t play the fiddle.

Collin grabbed a piece of dough and stretched it gently. “Until you have a theory.”

“That’s right.” Gran snatched the piece of dough from Collin and tossed it into the pot on the stove. It sizzled and crackled in the hot oil until it turned a golden brown. “You tell them the story they want to hear.” Gran fished out the fried bread with a slotted spoon.

“But that’s not honest.”

“It’s the most honest profession in this world. You only affirm what they already know.” Gran slit open the fried bread and added a pat of butter to the inside.

“But you trick them.” Collin handed Gran another stretched piece of dough.

“I stay alive.” Gran tossed it in the pot. The oil sizzled and hissed. “How many north winters could a fortune-teller survive if she didn’t play to win?”

Gran placed the two fried breads on Collin’s tin plate and held it out to him. A signal that he could start, so long as he continued to do his part.

“Sometimes people can only believe in themselves after someone else believes in them,” Gran said, sitting down to the table after all the dough had been fried. “After they hear their story told.”

“How do you know if the story you told is the right one?”

“They tell you.” She tore off a piece of her fry bread and popped it in her mouth.

“How?”

Gran gave Collin a pained look while she finished chewing. “Repeat it back to me.”

“Context. Information is all that matters.”

“It’s as precious as gold. And people give it away, every day, every moment.”

The snow blew hard against the window, but the prism glittered in the cold winter sun. Little rainbows decorated the kitchen table. They were all that decorated the table.

“I don’t want gold. I want more fried bread and butter.”

“Then you can’t afford to be so foolish. Only old grans make fried bread for little boys with faces covered in bruises. You need to be more careful next time. You know what trouble is now. Hurt, fear, pins pricking the back of your neck. You must learn what it looks like. How it smells. What it sounds like. Do you understand?”

Collin nodded.

“Good. Now tell me. What do you hear?”

***

He heard men, mostly the young privates, some a half-dozen years younger than his twenty, screaming in pain. Explosions ricocheted so close that Collin would have torn his own ears off from the ringing if he’d had a spare moment. The medic made sure he did not. And in the days (and years) that followed, it was not the sight of blood that haunted him, but the metallic smell of it. Fresh but insolently stale too. Dried on his forearms, still wet on his fingers.

“Am I going to die, mate?” the private with the patchy mustache asked. Collin tried to read him in an instant and formulate a theory for what the wide-eyed youth, with blood soaking the front of his uniform, wanted to hear. Collin didn’t know, but his comrade had asked for words, and, Mars, he deserved them if this was his miserable end.

“Only for a moment. And then you’ll live forever in the Great Beyond. Where there is only light—”

“And no turnips.” He coughed out blood, and drops of it landed on Collin’s face.

“No. None.” Oh hellfire, Collin didn’t know what to say. “And no mud or freezing rains.”

“And butter and fig pudding at every meal.”

“That’s right. And you pick who you share it with. Every time.”

***

“Every time,” the lieutenant colonel repeated.

Collin was standing in the road outside his camp. He’d done everything he could to ensure that he’d never get his boots caked in mud again, but here he was, four years after getting out of the medical corps, standing on a country road so destroyed by the wind and sleet that no sane person would venture onto it for another six weeks. Maybe seven.

The lieutenant colonel’s humor was certainly not improved for the ordeal. The old raisin seemed determined to make a point of it. “The enemy steals from us. They dishonor and disgrace us, and every time, they must be punished.” He circled the two boys lying facedown in the mud before unholstering his pistol and offering it to Collin. “You are the captain of this regime. The honor falls to you.”

It had been four years since Collin had held a pistol. The last one hadn’t been nearly so clean.

“Dispatch them. We can’t have the enemy stealing our supplies.”

Collin held the cold weight in his hand. Why did the lieutenant colonel have to come? Collin had done a good enough job keeping everyone out of trouble until now. They’d held their line, fought bravely, even waged a few successful campaigns under Collin’s command, but not enough to garner this kind of attention. Collin had made sure. His shoulders sagged as his boots sank deeper into the mud. “They can have my rations. Their crime is absolved as I freely give them—”

“The rations are not yours to give. They are the property of His Majesty—”

“I will not murder these children.” Collin’s fingers clenched tight around the pistol.

“If the enemy deems them fit enough to wear their uniform, then they will be treated as soldiers and deserve a soldier’s death. A bullet in the head for each of them, Captain. That’s an order.”

Screams chased away by weak whimpers echoed in Collin’s ears, even though the road was silent. The smell of blood already lingered and kept him company through the coldest nights. And the ringing. The damn ringing. “Turn them over,” Collin said.

The lieutenant colonel nodded to his men.

Collin would not look at the boys. He didn’t need a larger cast for his nightmares. “Your names and ages?”

The ringing drowned out their words. But he saw the lieutenant colonel blanch.

Collin nodded, still staring at the brightly polished author of so much fear and destruction in his hands. “Lieutenant Colonel, ask your men to step away. Every soldier should be allowed to face death on his feet.”

The raisin nodded, chest puffed up in pride. “Exactly so.” He motioned for his men to fall back.

“Behind me, gentleman.”

The lieutenant colonel chuckled. “A medic’s penchant for safety.”

“In wartime, it comes in handier than you’d think.”

Their boots slurched and gurgled in the mud. The wind blew a low moan, and Collin felt his heart keep time to an inevitability he wished he’d realized sooner.

It was time to leave the army.

The farm boys turned to Collin with eyes full of white.

“Run,” he told them as he raised the pistol to the sky and fired into the open air.

***

The princess’ footsteps announced her arrival long before the guard, the gaunt one who repeatedly misplaced the keys in his back pocket. “It appears you have a visitor.”

Collin rose. Six days had passed since he refused to execute those boys. The four spent in this prison had taught him a new kind of wariness. His eyes found the drops of chocolate on her tie. She was breathing quicker. Flushed cheeks. Something had changed.

“Thank you.” Ivy nodded her dismissal. The guard quickly ambled back to his pocket novel. “I apologize for the accommodations. I’ve arranged something more comfortable. If you’d be so good as to follow me.”

Collin would. The princess was better company than his memories. “I take it your morning went well?”

“Abysmal.” Ivy led Collin through the cloister and heaved open the sanctuary door.

“I’m not really dressed for church.” Collin buttoned the top button of his soiled and tattered shirt all the same.

Ivy strode quickly down the choir aisle. “And I’ve no patience for it this morning, but it’s the fastest route.”

A painfully thin friar spotted Ivy and waved her down. “Princess Ivy!”

“Father Michael.”

“If I might have a word. I’ve had the most distressing communication.”

Collin drew up casually to Ivy’s side, leaning his back against a column darkened with decades of candle smoke. He watched walls fall down in Ivy’s eyes, only to be shorn up immediately by her smile. It was an exceptionally winning smile.

“We’ve learned that His Majesty is displeased with the Archbishop of Ryland.”

“Oh?” Ivy shifted her dossier to her other arm.

“Apparently, the archbishop prays too much for His Majesty’s liking.”

Collin’s scoff bounced off of the centuries-old sculptures and stained glass, inspiring grave disapproval from the few praying friars.

Ivy’s smile disappeared into a look of sympathetic concern. “Surely not.”

“Would you be willing to speak to your father on our behalf? We are only too happy to pray less if it would—”

“Father Michael, I’m sure this is just a misunderstanding. Let me talk to my father, and I will sort this out.”

“Bless you, my child. Will you be attending the opera tonight?”

Opera in wartime? It was nice to know the capital had its priorities straight.

“Oh yes, and I think it best you invite as many parishioners as you can. My father does adore a crowd.”

“I’m sure several dozen members of my congregation would love to attend. However, there is the question of admission.”

“The balcony will be free to the public.”

“Excellent. However, a tangible incentive would be more enticing.”

Ivy’s shoulders tensed. “I’m sure there will be a public reception after the opera with several barrels of spiced wine and the usual fare.”

“Excellent, Your Highness. Excellent as always.”

“Good day to you, Father Michael.”

“And to you, my child. And to…” Father Michael took in Collin for the first time, no doubt noting Collin’s torn and soiled shirt. He raised his hands in a prayer above Collin’s head. “And to you, my son.”

Ivy pushed through the abbey doors and headed out into the west courtyard. “You are very quiet, Mr. Dobhareach.”

“I was listening. A lot was being said just now.”

“A lot is always being said. It would be nice not to be the one who had to say it for a change.” Ivy examined her pocket watch. It was a marvelously intricate, albeit tarnished, piece. An emerald inlay, if Collin had to guess. “It would also be nice if one didn’t have to answer for any of it.”

“Your Highness?”

“I’ll need an hour before the opera to coordinate the public reception. Thank heavens the shipment of ale arrived from the coastlands.” Ivy stopped outside what Collin imagined was the college garden. A beautiful magnolia tree had bravely bloomed early, emboldened by its tactical brilliance of growing in a wind-protected corner. Poor tree. Its blooms would shrivel in the next snowstorm.

Ivy opened her dossier and began to scribble. “My father has requested that you attend the opera with us tonight.”

“Has he?” Collin sauntered closer, curious to see what sort of notes Ivy took.

“I’d imagine you have no formal wear.” She looked up at Collin with a sly smile. She snapped her dossier shut and marched across the courtyard toward the common.

Collin followed. “Sadly, my dinner jacket was confiscated with my other personal effects when I was thrown in your prison.”

A group of fellows passed by in their green and vermilion scholarly robes. Ivy smiled and nodded. But her eyes were hollow and the shadows under them deep. They crossed the common, the dried and yellow grass accented with only the scantest tufts of foolhardy green clover. “It is not my prison, Mr. Dobhareach—”

“Dobha-reach,” Collin corrected. “You’re adding syllables that aren’t there.”

Ivy stumbled but quickly regained her footing. “It’s impossible to pronounce.”

Collin shrugged. “If you have a lazy tongue.”

“I’d take care not to insult the woman who haggled for your freedom.”

“Are you in the habit of taking in stray men from makeshift prisons and inviting them to the opera?”

“Mr. Dobhareach—”

“If I’m to be your date this evening, then you should know I go by my first name, as no one can ever pronounce Dobhareach. And captain is perhaps a more appropriate title than mister.”

Ivy twitched a black curl out of her eyes. “Let me impress on you, Captain…” She opened her dossier and riffled through the papers.

“Collin.”

“Yes, thank you. Let me impress on you, Captain Collin, how delicate a situation this is.”

Collin’s gaze settled on Ivy’s neck and wandered to her tweed jacket. What was she doing out in the elements in only a jacket? Gran wouldn’t have stood for such nonsense.

Ivy’s fingers on Collin’s jaw quickly redirected his attention. “My father takes great stock in first impressions.”

“I don’t think there is anything I could do to persuade your father that I am essential to winning the war.”

“Not with a torn shirt and that attitude. Try to keep up, Major.” She turned off of the main avenue, down a small alley.

“It’s captain.”

“I’ve promoted you. I can’t have a lowly captain leading my task force. Now, tell me how you kept all your fingers while still managing to blow up so much of Olcceart’s artillery?”

Collin’s heart beat faster. He raked his fingers through his hair. Mars, this would be funny if it were happening to another man. “Working with explosives… It pays to be risk-averse.”

“Explain.”

A particularly bitter, far-reaching wind found them in the shadowed alley. Why didn’t she have a coat? Collin would have offered her his own, had he one to offer. “Explosives can be highly unstable. A single blunder can be deadly. A few spilled drops could take off your hand. In the quiet confines of a workshop, there is risk. How much more so in the theater of war? I didn’t want to lose any of my extremities. I didn’t want to be responsible for the lost limbs or lives of my…” Of the other boys who’d stood with him shoulder to shoulder. The ones who’d by now perished, with the rest waiting out the winter to do the same. “I found a way of making nitrated glycerin more stable.”

“The putty?”

Collin nodded. “Adding it to kieselguhr made it practically inert.”

“By raising the activation energy?”

“Just so.” What would Gran make of her?

“An inert explosive isn’t very useful.”

Collin shrugged. “A detonator changes the equation. Every time.”

“It must be nice to work in absolutes.” Ivy directed Collin down a busy street. Cabs and hacks jostled one another. Horses shook their bells and flicked their tales against the staccato of their hooves. She had to shout to make herself heard over the din. “Your detonators and knowledge of explosives will be a real advantage, not that we have many. I won’t sugarcoat the situation.” They turned down a quieter street. “We face an industrial nation, mobilized to outfit a conquering army with the latest technological advantages.”

“Yes, their machine weaponry is impressive.”

“And effective.” She tucked the dossier under her arm and gripped her wrists behind her. “The Republic of Olcceart was ready to win the war with the first invasion. They have prolonged the fight because it is a boon to their economy and national pride.”

Convenient to leave out that it was her father and his ridiculous trade war—and idiotic posturing—that had led to that first invasion.

“Although, I do wonder if there is not something devious going on. A clandestine goal to decrease their population. Some of our neighbors appear preoccupied with purifying their kingdoms.” Ivy’s voice faltered. She retrieved a pair of leather gloves from her dossier and tugged them on. “The rumors I’ve heard of forced marches and exile… It is a dangerous time for our fey friends.”

Collin wanted to know the rumors she’d heard. He wanted to know how much she understood. He wanted to know if she couldn’t sleep at night because of it. If she couldn’t sit with a quiet cup of tea alone now. If she had woken up bone-tired but too scared to fall back asleep because she had dreamed the very worst. And knew it was real.

A part of him, the part deeply bruised from all he’d seen and survived, wanted to reassure her that her fears were unfounded. But Collin couldn’t outright lie. He could, however, admire how soft her lips looked.

She was off again, and Collin had to jog a few paces to catch up. They turned down High Street, past blocks of smart townhomes, the prettiest outfitted with window boxes filled with white and purple flowers.

“Aren’t the violas charming?” Ivy asked. “You think I’m like them, don’t you? Pretty little things sheltered away and oblivious to the struggle.” She fussed over the button of her glove. “The horrors we are facing.”

“Have you been to the front, ma’am?”

She continued to struggle with the button. “No.”

So she read reports and imagined she knew enough to play with the fates of so many men, pretending they were little more than toy soldiers in a ridiculous skirmish over ice fields!

“Four years ago, at the start of the war,” Ivy said, “I toured the hospital tents.” She squinted into the sunshine. “For all of twenty-four minutes, before I was escorted back to safer ground.” She shivered in the wind. “Papa was furious, but I had to do something.” She once again turned her attention to the loose button on her glove. “One does not forget shed blood.”

Collin watched her continue to struggle. She’d seen it, heard it, smelled it. It haunted her too.

“I begged to return as a nurse, a mechanic, a secretary, anything. But the safety of a princess is weighed differently than that of our boys,” she said grimly. “Even if there are twelve of us.”

Collin approached and offered his assistance with the stubborn button.

Ivy accepted. “Papa deigned to let me help with the paperwork he ignores. But helping with his dispatch boxes is not enough, not when young men are dying, and they spend their last moments covered in their own blood, talking of turnips.”

Collin’s hands slipped from the button. He fumbled and held Ivy’s gloved hand in his own. He dared not look into her eyes.

“Every time I bring this, or any bit of bad news, to Papa’s attention, he changes the subject, or he tells me that I needn’t worry, but when I press, he bellows, ‘Then bring me a solution.’ You are my solution, Major.”

Collin had to say something to change the subject. “The violas are a favorite of Her Highness?”

A frown accompanied her impatient huff. “Why must every woman have a favorite flower?”

She was going to make him work for this bit of intel. “Then you prefer roses? Tulips? Gardenias?”

She walked on. “The sweet pea, if you must know.”

Collin grabbed his elbows and hugged his arms to his stomach. His lungs became poor servants. “My Gran grew sweet peas.”

The sweet pea was a curious flower known for its scent and not its form. And the memory of the smell ferried Collin back to the barefoot kingdom of a little boy. Gran would soak the seeds the night of the first autumn frost, and they’d plant the swollen black pearls the next morning. He had to say something, or he’d start to cry. “Early spring days like these, ones that could easily be mislabeled as late winter—”

“Where you want nothing more than to hold a cup of something hot in your hands.”

Exactly! “Where the balance of your life hinges on dry, wool socks.”

“Where you imagine the sun has lost its strength.”

Mars, but she was forlorn. Her smile rivaled the ones he’d seen at the front. “These were the days that Gran and I would look for the cotyledons among the crocuses.” They’d check the sweet peas’ progress daily. Gran had taught Collin when to tie the sweet peas to the fence post. When they were young. Before they made up their mind to be troublesome.

Ivy turned up a new row of dazzlingly white townhouses.

“How do they keep the coal smoke off the stone?” Collin asked.

“They don’t. The facades are washed regularly. I read the details of your desertion.”

Collin winced. Was there really nothing better to talk about from his file?

“You impressed me, Major. If we win this war, and win we must, and the dust settles, and we go home and discover that we are no longer capable of gentlemanly sensibilities”—Ivy shrugged—“then we’ve lost something even more precious. You agree?”

“Emphatically.”

Ivy nodded. She turned down an alley.

Collin followed. She almost had him convinced he was a hero. That wouldn’t do. “War is too easy an excuse to use a fellow as something less than human. And war makes the necessary functions of intelligence—spying, assessments, interrogation…”

Ivy turned pale.

That was better. “It makes it too easy to use these for one’s personal gain.”

Ivy jabbed Collin’s chest with a gloved finger. “You were not sufficiently stressed to make my polygraph helpful. I did what I could.”

“You did what you wanted.” They had that in common at least.

“I don’t believe in violence, Major Collin, but you have me reassessing my stance. Slapping you now seems like a good idea.” Ivy marched up the stairs to a slim residence shouldered between far larger real estates.

“A gentleman knocks,” Ivy mumbled.

Collin reached around Ivy on the little stoop and lifted the brass knocker up and down.

A woman in a turban opened the door. “Ivy!” she screamed, embracing the young woman. “It’s been ages. How are you, my dear?”

“Fine, Auntie. Fine.”

“Lies, my dear. I see the dark circles under your eyes. But come in. Come”—the turbaned woman turned to Collin, and her eyes danced—“in,” she commanded, ushering Collin into her home.

Incense filled the salon. And art. Paintings and silver-plated glass photographica filled the walls. Exotic orchids and vines spilled off of the slender tables. Books lay in stacks. “I’d offer to take your coats, but goodness, you are without them.”

“Which is why we’ve come. Auntie Olivia, this is Major Collin. He is Papa’s guest at the opera tonight, but alas he has no dinner jacket.”

Olivia turned an appraising eye to Collin. Given his sorry state—torn and soiled shirt, threadbare and filthy trousers, matted hair filled with coal smoke, and dirt, sweat, and yellowing bruises covering most of his skin—it was absurd to be discussing dinner jackets. Gran would have told Collin to wait outside and doused him with a bucket of water before she greeted him.

“Major?” Olivia extended her hand graciously.

Collin pressed it warmly. He liked this maternal woman. He liked even more that she belonged to Ivy somehow. Collin bowed over her hand. An extraordinary ring of andalusite and sapphires adorned her index finger.

“Major, this is Madame Olivia. She was—”

“Is, my dear. Is,” Olivia extolled. “Death does not erase friendships.”

“—a dear friend of my mother’s. And has been a godmother to me in her absence.”

Collin’s brow furrowed. He should have remembered the princess’ family history. He should have known when and how that mother had become absent. Olivia would know. She’d know all the gossip about Ivy and her family. And judging by her open, friendly manner, she’d be more than willing to share with Collin. It was too easy. Ivy would have to be warned about revealing so much information in the future. “A pleasure, Madame Olivia.”

A wide smile spread across Olivia’s face. “A joy, Major. Now, then, tea, coffee, cocoa imported from the far-off forests of the Easterlies?”

Collin knew better than to refuse friendly hospitality. “Tea, thank you.”

“None for me, Auntie. I must be going. I’ve a promise of spiced wine I must keep. Would you please help the major prepare for the opera?”

“I’d love to.”

“Thank you. Is Ottis in? I’d love to say hello before I disappear.”

Olivia busied herself at the tea service. “Ottis is out inspecting the tulips’ progress at the abbey, though I told him there is none to be found yet.”

“Will you give him my love when he returns?”

“I’ll treat him to his favorite biscuit in your honor.”

“And would you join us in our box tonight?”

“Alas, my dear, I have important preparations to make for an upcoming expedition.”

“And here I am demanding last-minute favors.” But not apologizing for them, Collin noted. “Safe travels, Auntie.” Ivy bussed Olivia’s cheek.

“Take one of my coats, Ivy. It is too cold, and you are too small to be playing this sort of game with the wind. You don’t know the wind the way I do. He has no compunction when it comes to young ladies. The major would agree with me, but as he is coatless himself, he’s hardly an authority on the subject. We will soon remedy that, aye, Major?”

Collin agreed.

Olivia rolled her eyes and gestured an order for him to assist the princess. He readily complied, joining the princess at the armoire near the door. She’d already made a selection from among the jewel-colored offerings.

“May I?” Collin asked, taking the coat and holding it open for the princess. Ivy hesitated before she shrugged into the indigo wool. Collin adjusted the collar, smoothed the shoulders. His hands tarried, and he was seized with the impulse to hold this young woman close.

Olivia clasped her hands together. “Just lovely.”

Ivy met Collin’s eyes and had the audacity to smirk. “Yes, it’s breathtaking.”

Collin flushed. His arms retreated to his sides.

“Auntie, where did you find this wool?”

“Oh, you know me.” Olivia turned her attention to Collin. “I’m always interested in sponsoring the young and talented.”

Ivy nodded. “Now out of my way, Major. I’ve more pressing business than spiced wine to see to before tonight. Budgets. Broken chimneys. And an avalanche of correspondence from our easternmost charities.”

“Charities?” Olivia brought the major a steaming cup of tea.

“Hospitals mostly. A few libraries. Even a poorhouse.”

He felt himself pale. Pins prickled the back of his neck. What did she know? More important, what did she suspect?

When Ivy had left, Olivia rounded on Collin. “Don’t worry, Major. When I’m done, you won’t even recognize yourself. Now, then, let’s start with your mustache.”

It was a simple yet elegant plan. The rifle was not concealed but hiding in plain sight. One in a lineup of many props for the opera that evening. However, this rifle was loaded. And fitted with a clever telescope that would make the task of aiming a bullet at King Rupert’s skull all the easier.

“Where have you been?” Trina asked.

Ivy struggled with the buttons of her vest. “Oh, Trina, you look lovely!”

Wearing her best violet silk, Trina was serene, poised, lovely.

“Did you have a go at the abbey’s organ?” Ivy asked.

“Mm-hm.” Trina helped her sister with the row of buttons down her back. “I did. Right after I removed a robin’s nest from the C-major pipe. I don’t know what those monks have been doing for the past six months.”

“Hiding so they don’t get drafted.” Ivy fumbled with the buckles on her boots. “Did you save a dress for me?”

“I did, except Daphne stole it.” Trina handed Ivy an impressively ruffled petticoat.

“Trina!” Ivy wiggled into the petticoat. “What in heaven’s name am I going to wear?”

Trina heaved a green gown out of the armoire.

“No!”

“Ivy darling, this is what happens when you wait until the last moment to change.”

With eleven sisters, it was what happened. Wardrobes were pillaged. The most fashionable styles conquered. The most flattering colors captured. The posturing of victorious strategy decisive. “You know I can’t stand green,” Ivy said, tossing back the dress.

“Green suits you, Ivy.”

“It doesn’t matter. If your name was a plant as well as a color, you’d understand why I am weary of the association.”

“I thought only Papa still teased you when you wore green.”

Ivy huffed, stepping out of her pinstripes. “Papa still thinks I’m twelve years old.”

Trina had the gown up and over Ivy’s head before Ivy could say another word. “Has Papa approved of your strategy?” Trina concentrated on lacing Ivy into her gown.

“No. I didn’t even have a chance to explain. Papa was all, ‘I wrote an opera. Are you coming to the opera tonight, Ivy? I wrote it!’” Ivy gripped the back of her desk chair.

“Breathe in,” Trina instructed.

“Why do we do this to ourselves?” Ivy said, holding her breath.

Trina tugged hard on the laces of Ivy’s bodice. “Because it’s fun.”

“Did you know that Papa wrote this opera?”

Trina paused before tugging the laces with renewed vigor. “No. But I do know that Berlios wrote the score, and he is wonderful.” Trina tied the laces extremely tight.

“If Berlios is so wonderful, why don’t you marry him?” Ivy teased. The same way she had teased Trina back when they’d worn their hair in braids with matching ribbons.

Trina tossed Ivy a jeweled necklace. “Well, for one, he is conveniently taken and has been for at least twenty-five years. And two, he’s not an organ enthusiast. I keep trying to persuade him to write more for our organs, but he never does. Now hold still.”

Before Ivy could object, Trina had threaded a circlet of silver leaves into her coiffeur. “Oh no, Trina. The injustice of this is too much.”

“But you look so pretty! Besides, Papa is too nervous this night to say anything.”

Ivy struggled with the clasp of her necklace. “That doesn’t sound much like Papa.”

Trina shrugged and turned her sister toward the electric lamp. She opened a pot of red cream.

Ivy shook her head. “Absolutely not.”

“I swear I will not overpaint the way Gwen does.”

“No.”

“But, Ivy, the lights will be so dim, and if you aren’t done up like the rest of us, you’ll stand out like an old—” She cut herself off.